Figural Space vs. Figural Objects

The diffeence between techn ical and functional third spaces.

There was a time when I was obsessed with architecture—the buildings themselves, their shapes, their details, their stories. But then, in 2007, a Georgia Tech student said something (almost offhandedly) that rearranged my brain: architecture isn’t just about what happens inside a building; it’s also about what that building does to the space outside of it. And suddenly, there was a shift in what I truly cared about.

We hear a lot about how America doesn’t have third places—but that’s not exactly true. Technically, there are places we could gather: the edge of a grocery store parking lot, a strip of grass beside a road, or a park twenty minutes from home. But there’s a difference between places where gathering is allowed and places where it actually happens. The power of third places isn’t just in their legality—it’s in their ease, their spontaneity, their invitation. So maybe the better question isn’t do they exist, but why aren’t they used?

Understanding the concept of figural space helps you see the difference between a place where you're allowed to meet up and a functional third space where people actually do meet up.

It starts with the public realm; the space between buildings. It might look like a French plaza or a quaint Tokyo street in a Studio Ghibli movie—but it can also look like a Kroger parking lot. But third spaces are almost like fruit trees; a healthy one bears fruit. And if a third space isn’t full of lively interactions throughout the day, something is wrong. Where’s the fruit? Why aren’t people there?

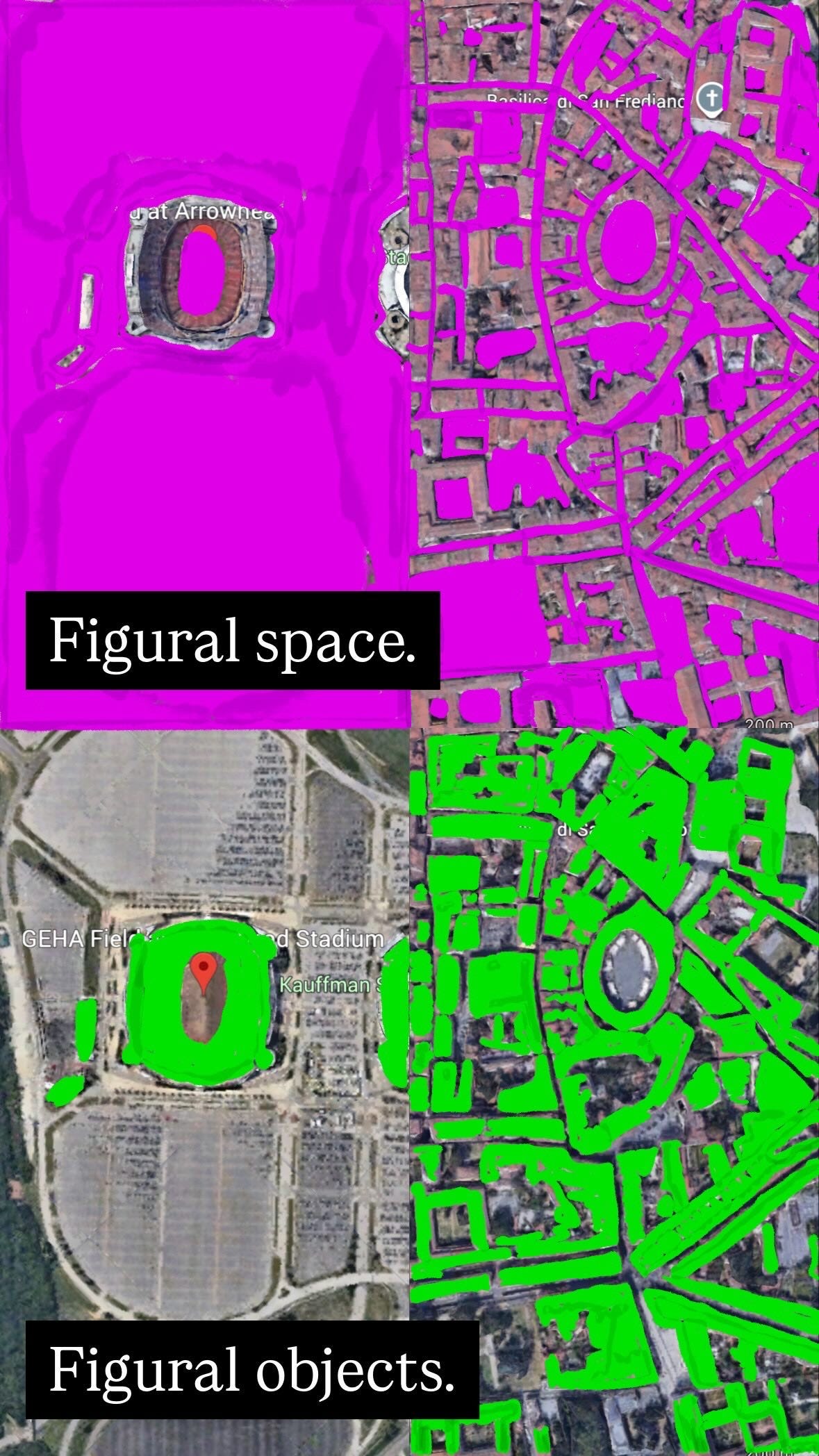

If you look at an old medieval town center and highlight the space between built objects, that's the figural space. If you highlight the buildings instead, those are the figural objects. Now do the same thing with a sports stadium in the U.S. First highlight the space, then the object. What you’ll notice is that in America, we often have large amounts of untethered, disconnected space surrounding a single object.

Compare that to an old-world town center, where you’ll see interestingly shaped spaces created by the buildings themselves. For most of history, architects emphasized the space outside the buildings just as much as the buildings themselves. That is what I mean by figural space: the public realm matters.

Often, buildings would take odd and unsatisfying shapes in order to create the types of streets and public squares people actually wanted.

Contemporary architecture has flipped those priorities. It’s obsessed with the object itself. “Starchitects” focus on skyline-defining buildings or something with the Bilbao effect—the idea that a building is so visually striking, people come just to see it. But these figural objects do little to nothing to support community outside their walls. They’re meant for arrival, a few photos, and departure.

On the flip side, the places we like to spend time in have a sense of place. We gather, exhibit more pro-social behavior, and are generally happier in these spaces. So what are some attributes of wonderful spaces?

Good places are made of lots of small things.

Places we love are full of lots of little things. Both to look at, and to do. a variety of businesses will make a space functional to visit for multiple reasons. If you need to both buy a gift for someone, groceries, and pick up dry cleanings, it helps when they are all in the same spot. And while you’re there, you can stop and get lunch. If you see someone, you might invite them to lunch and join them for some of their errands. All these different uses increase what commercial real estate people refer to as dwell time. And dwell time is a determining factor in the value of a property.

But perhaps the value of all these little things can be better seen by looking at the weakness of the opposite use of space. Consider a large single-use building. It attracts a certain type of person to a certain type of need usually at a certain time of day. This creates dead times, and busy times, and is prone to one big failure that would economically handicap that spot. Even as cities modernized with bigger buildings and grander purposes, we see that lively streets will consiste of a bottom floor that has constant interaction to the street.

Dwell time in commercial real estate refers to the amount of time a customer spends in a particular space—like a store, shopping center, or plaza. Higher dwell times often indicate stronger customer engagement and can lead to increased spending, making it a key metric for retail performance and placemaking strategy.

Good places are free.

When I say good places are free, I don’t mean untouched by capitalism. In fact, there are strong free-market arguments for plazas and squares: free gathering spaces attract people—and people attract more people. Want more customers? It helps to have others around, even if they’re not buying anything.

Now imagine a mall in the 1980s—but instead of a lively mix of people between stores, security escorts out anyone not clearly shopping. What makes an empty mall so eerie is the silence of its in-between spaces—spaces meant to be filled with life. Eventually, we even had a term for those who lingered: mall rats.

Malls were always destined to be consumed by commercialism. Though designed to mimic the energy of a town square, they weren’t rooted in real life. No one lived there. They lacked true social infrastructure. In the end, it was a snake eating itself—an attempt to simulate community just to sell more stuff.

It’s telling that Victor Gruen, the Austrian architect behind the first successful American mall, was disillusioned by what malls became: pure commerce without community. Reflecting on the sprawl and car-centric development they inspired, he famously said, “I refuse to pay alimony for those bastard developments.”

The irony of many American cities is this: we’ve criminalized lingering (loitering), so the only people who loiter are those with nowhere else to go. As a result, our public spaces feel hollow—requiring constant programming and festivals just to bring people in.

True third places are free to inhabit, even if they’re commercial. There’s no time limit, no pressure to spend. And often, the most successful places—financially and socially—are the ones where people simply feel welcome to stay.

Good places protect you from exposure.

Look at the first image once more. The public realm is incased in buildings. It creates outdoor spaces that feel like outdoor rooms. Not only do buildings give actual protection from exposure to things like the sun, this sense of safety created by this enclosure actually registers on a psychological level; well-proportioned buildings have the ability to create a sense of safety.

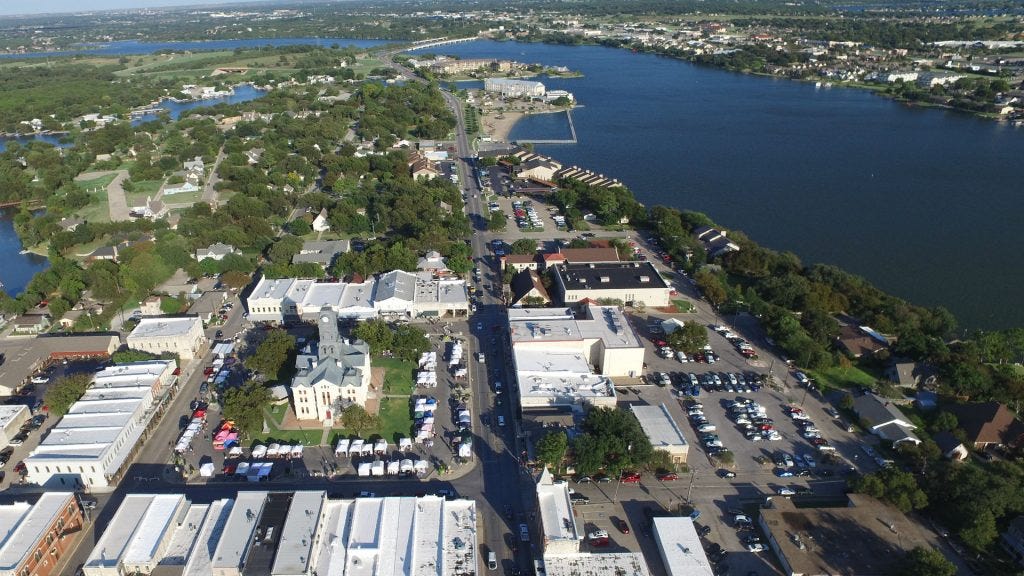

In the image below, we see two examples of the public realm—neither accidental, but shaped by policy. When large areas are dedicated to the temporary storage of cars (parking), buildings are pushed apart, eroding any sense of enclosure. The resulting expanses of impermeable surface intensify weather extremes: heat reflects, water pools, and shade disappears. The design quietly suggests what it values—movement by car—and discourages what it doesn’t: spending time outside.

Good places are interesting.

This almost goes without saying: we like to spend time in interesting places. The famous observational urbanist Holly Whyte noted that visual enjoyment is a secondary use of any well-frequented space. At the top of that list? People-watching. We love noticing details and delighting in eccentricities.

Window displays and architectural ornamentation are, in part, marketing tools because they tap into our innate curiosity. We're drawn to variation, pattern, and beauty. And in true figural space, that interest isn't generated solely by ads or clever branding, but by the built environment itself. If you want a place that brings people together, make it interesting.

This requires empowering businesses at the smallest possible scale; quirky one-off shops and merchants willing to inhabit odd buildings and corners. Great streets feel full, and that often means people adapting to what's available. Mobile merchants, food trucks, tents, and pop-up shops not only add visual interest but also provide an accessible first step for aspiring entrepreneurs.

What’s keeping interesting places from forming?

Setback requirements can limit a building’s potential to serve as a noise buffer, provide shade, or define the edges of the public realm. By forcing buildings farther from the street and each other, setbacks often negate these benefits. They can also make irregularly shaped lots undevelopable—leaving them vacant or turned into parking lots.

Parking minimums aren’t just a poor use of land—they create costly hurdles that only well-resourced developers can clear. Smaller, independent businesses often can’t overcome these barriers, making it harder for the kinds of quirky, character-rich places that give neighborhoods their charm to take root.

Overly wide streets: when you maximize a place for car throughput, roads become overly wide and other features have to be sacrificed. Awnings, tents for markets, and trees often are traded for an extra lane for cars.

Zoning that separates uses kills vibrancy. Mixed-use areas stay active all day—unlike business zones that boom from 9–5 and go quiet after.

Restrictive building codes are often rooted in exclusion, not safety. Many were created in bad faith to discriminate, and modern technology has made even the well-intentioned ones increasingly outdated.

What makes a place worth spending time in is how it is shaped by the buildings around it. With little options for regular people to contribute to the built environment, we often see big investments whose aim is to create a skyline-defining building or an interesting object at which to look. Though I didn’t even touch on how many of these objects aren’t particularly useful to inhabit, they also affect the outside world. We should, instead, think first and foremost on the relationship of our buildings to the built environment, and take a close look at policies which unintentionally limit their public good. And though it is not necessary for there to be an economic reason to do so, these sorts of places with small local businesses create strong, resilient economies and, in the end, keep more dollars local.