Striving for Less, but Better: Post-Satisfice-Less & Skeuomorphism

Tactical and practical ways to engage with your public realm

Note: This is a part 1 of 2, but it lands with practical applications of its own.

A Quick Puzzle

Imagine I gave you the lego below and asked you to bring the blue plate to level in under a minute with nothing hanging over the edge of the bottom plate; what would your strategy be?

Most who answer this are primed by the presence of other prices and begin strategizing about which pieces to use first.

Addition Bias

However, the easiest option would be to remove the few pieces that are already in place. Why don’t most of us see that right away? (If you did see that right away, you can comment below and let us know how cool you are.)

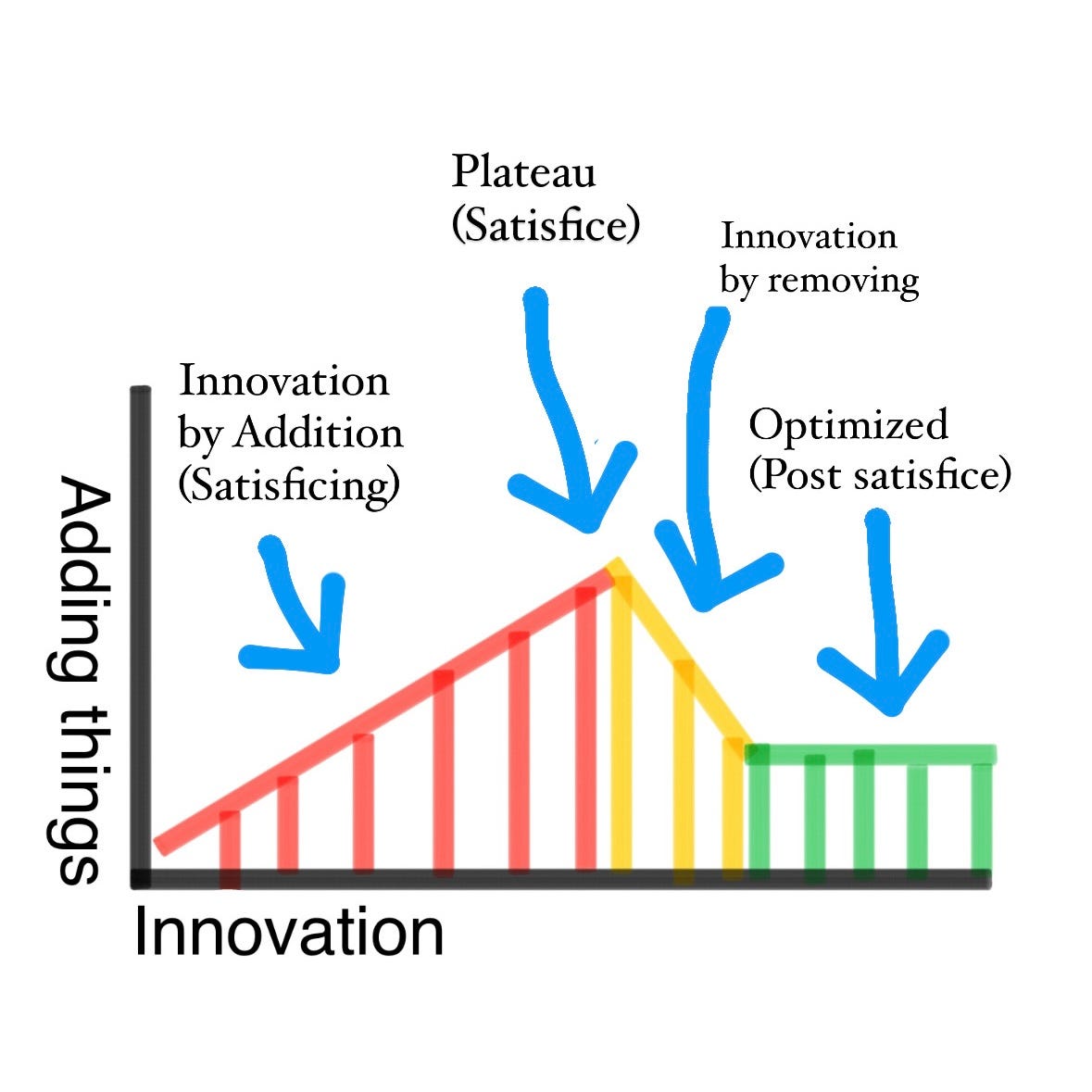

This is known as addition bias: the proclivity to add to a process or problem in order to solve it. For millennia humans have succeeded by adding to solve problems.

Cold? 👉 Add fire!

Wet? 👉 Add Shelter!

Need food? 👉 Add a trap!

And as a rule, this helps! Biases exist in part because they work. If you want to solve a problem, trying stuff until it’s resolved works 99% of the time.

Industrial Revolution

Though there was an ever-present addition bias from human evolution and adaptation, the scientific method codified it. The Industrial Revolution is sort of like the scientific method applied to economics. This process of adding has given us so much technical advancement.

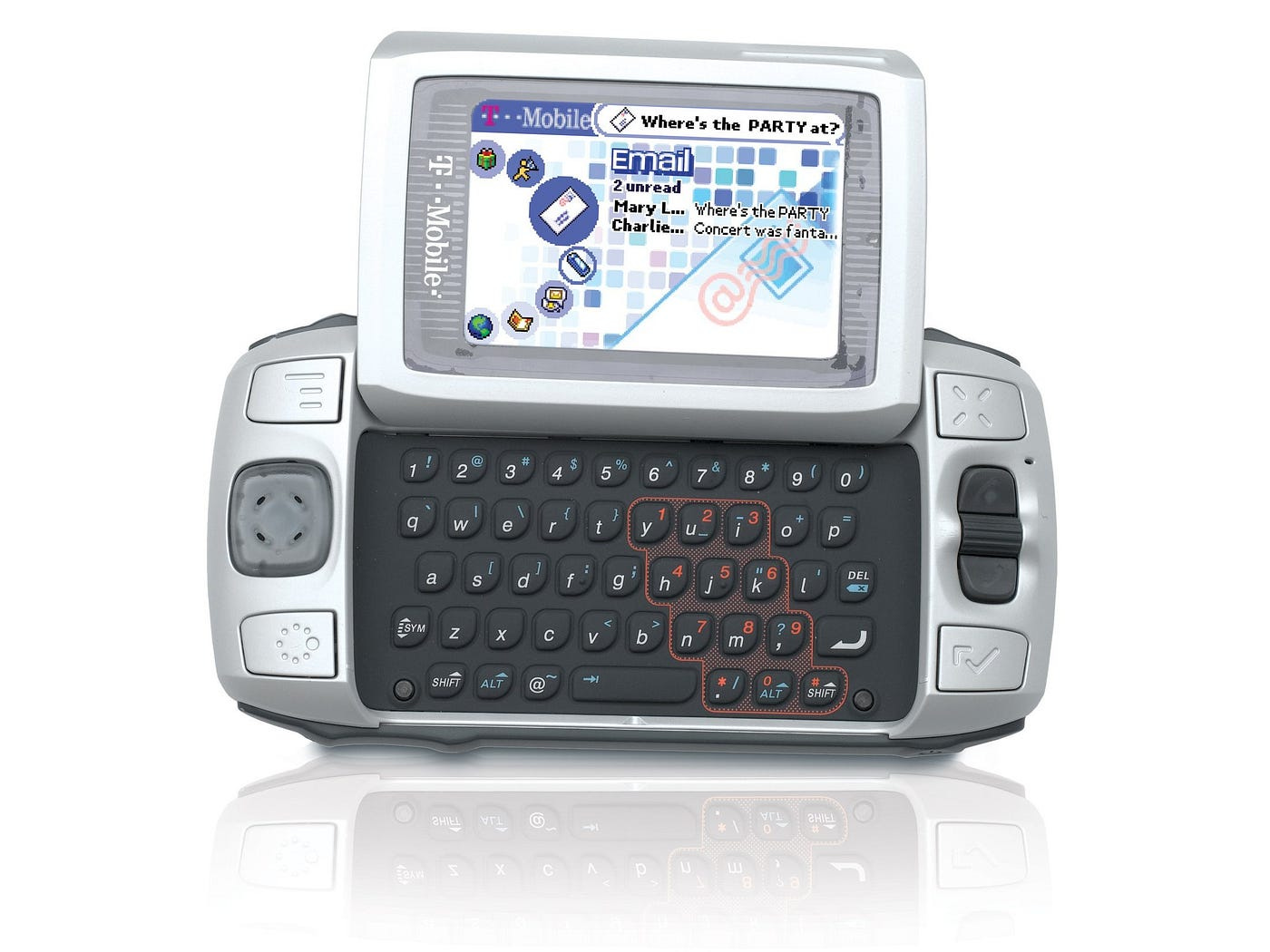

txting bff Jill

But there is a breaking point. Things designed by perpetual addition get clunky, and hog resources, and often don’t make sense. This is where there is a substantial opportunity for innovation that is often missed.

Consider cell phones in the early 2000s. There was an arms race to solve the problem of cell phone design. As texting (and later the internet) was brought to our phones, there was a need for both a better screen and keyboard.

If there’s a big screen, the keyboard was too small.

If there’s a big keyboard, the screen was too small.

If both were big, the device was too big.

If they added innovative moving/hiding keyboards, the phone became more fragile with moving parts.

At one point, it was assumed Blackberry had won; a small keyboard with elevated corners for each key that made it easier to hit a single key. Yet, the phone that was to unseat Blackberry didn’t have a better keyboard, it had no keyboard at all.

Apple

Apple’s removal of the keyboard was a great example of a term that you’ve probably never heard of: post-satisfice-less. The idea is this; in a world of clunky innovation, figure out what works, then figure out how to do it with less.

The word satisfice is a portmanteau of the word satisfy and suffice. Meaning, it’s good enough. Let’s use a work schedule as an example of how this works in real life. Let’s say you are the head of customer service at a tech company and spend 20 hours a week in meetings and the company customer satisfaction is at at 95%—which is where you want it. You’ve found the ‘satisfice’ amount of meetings. But imagine you start consolidating certain meetings, making some shorter, or even cancelling them all together and retain the customer score of 95%; you’re hitting your goal with less (post-satisfice, less).

Now, you may use that extra time to potentially better serve your customers or solve other problems. When Apple made a phone that was all screen they increased their abilities. This small change shifted economies and cultures. There’s a chance you’re reading this on an iPhone.

Why does this concept matter?

There are things broken with our cities which we are trying to solve by adding more things to them. For example, I attending a meeting yesterday regarding upcoming zoning changes and the proposed document was 276 pages long. The meeting took two hours and could have been spent entirely on 1-2 questions regarding the legal ramifications of the slightest wording. Yet, a local non profit pointed out these changes did very little to address the problems we originally set out to address, most notably; housing scarcity.

Many problems we face in our cities now can likely be solved through removal rather than addition.

Building examples

👉 Removing parking minimums

👉 Removing set-back requirements

👉 Removing restrictions on mixed-used zoning

👉 Removing lot size minimums

👉 Removing restrictions on multifamily homes

Transit examples

👉 Removing stoplights where a stop sign would do (four way stops are way cheaper and safer than stop lights in an urban environment)

👉 Removing one-way streets. Changing a one-way to a two way will slow down the average speed by almost 7 miles per hour alone

👉 Removing signage and striping altogether: The term is ‘naked streets,’ but in some places removing signage and striping creates an ambiguity (“Should I be driving here?”) that causes drivers to navigate more carefully. I made a video on it.

👉 Removing a lane: most four lane to three lane conversions reduce traffic and speed

Obviously, there’s more than just removing that happens in some of these situations. But, by and large, they’re making the system simpler.

So what does that mean? Next week, we’ll touch on part 2: Skeuomorphism, and how to facilitate change.

P.S. If you’re interesting in learning more about this or going deeper into this, I first heard about this idea in the book Subtract, by Leidy Klotz.