The typical American strip mall isn’t beautiful.

At least, it’s a different type of beauty. It’s so plain and utilitarian that it holds a quiet potential — a kind of understated promise.

And in that way, it’s beauty is in a latent power, waiting to be actualized. This issue is about releasing that power.

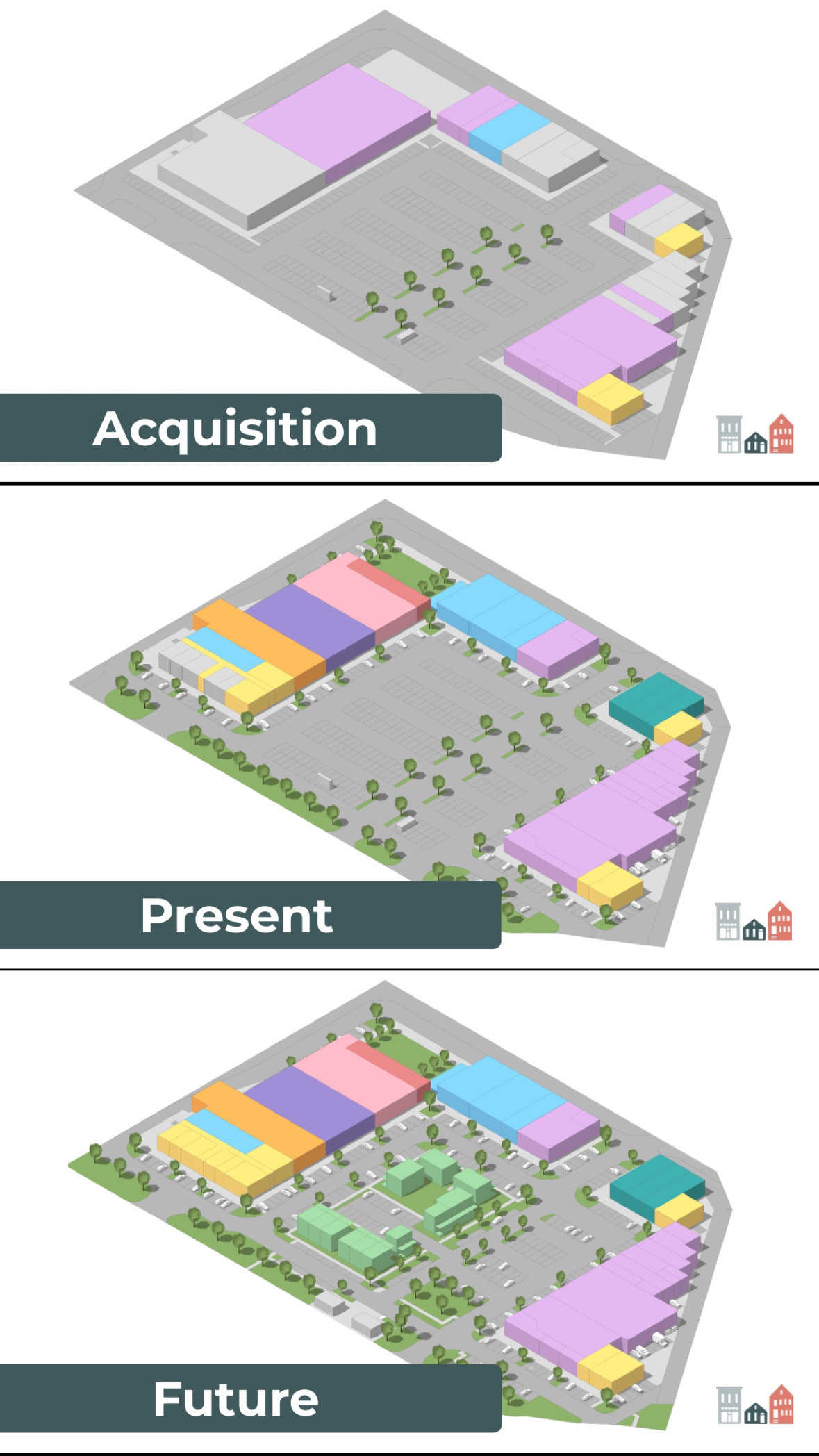

Wheatland Plaza in Duncanville, Texas is unremarkable and not unlike an ugly strip mall near you. But in the last few years, it’s increased in value 8.3x while simultaneously increasing opportunities for small businesses.

It’s a project led by Monte Anderson, of Options Real Estate, with help from planning consultant Jim Kumon, and both are founding members of Neighborhood Evolution. And on paper what might look like magic is repeatable and something other communities can tap into.

If there was one Substack I’ve written that I think you should read through, It’s this one. Here’s what we’re going to cover, and feel free to skip to the part that intrigues you:

The plight of these empty and dying malls.

The challenge of retrofitting.

How to align investors’ desires with community needs.

Not quite Utopia, but sort of black magic.

The plight of these empty and dying malls

A strip mall is not much to look at — rows of faded awnings, blank walls, and tired parking lots. Yet, like a forgotten stream, it holds a quiet potential. When its anchor store leaves, the air seems to shift — foot traffic slows, lights go out, and soon the storefronts gather dust. What once felt ordinary now feels empty, almost haunted.

This phenomenon, sometimes referred to as the "dead mall" syndrome, has been observed across the country. For instance, the closure of JCPenney at Charleston Town Center Mall in West Virginia raised concerns about the mall's viability, as anchor stores play a crucial role in attracting shoppers to smaller retailers.

The decline doesn't stop at the mall's entrance. Surrounding neighborhoods often experience reduced property values and diminished community engagement.

But the true tragedy is not in the emptiness — it’s in the slow unraveling of what once held the place together. Small businesses close, property values dip, and a sense of neglect takes root. The people who once lingered there scatter, and the strip mall becomes something between a monument and a warning. This cycle of decline underscores the importance of adaptive reuse strategies to revitalize these spaces, transforming them into assets that serve evolving community needs.

Adaptive reuse is the process of repurposing an existing building for a use different from what it was originally designed for, often to meet modern needs while preserving the structure's historical or architectural value.

The challenge of retrofitting

These spaces are often defined by their stark, utilitarian design — flat, windowless facades and sprawling asphalt parking lots that contribute to heat islands and poor stormwater management. The sheer size of many vacant units, built to house large retailers, makes them difficult to divide or repurpose for smaller businesses, community spaces, or housing.

Additionally, the aesthetic of these structures — characterized by blank walls, faded signage, and a sense of neglect — can deter potential tenants and investors. Successful adaptive reuse projects must contend not only with these physical barriers but also with the social stigma attached to these decaying spaces, transforming them into vibrant hubs that serve evolving community needs.

And in this sense, Wheatland Plaza was no different. As you will see, however, it’s past wasn’t its destiny. And it acts as a road map to how cities can do soemthing similar with their dead malls.

How to align investors’ desires with community needs

Wheatland Plaza is 7 acres and was 97% impermeable surface — mostly concrete. It had disproportionately large storefronts that were hard to keep occupied. Investors need to make a certain amount per square foot to justify a purpose. Smaller businesses can’t afford the larger empty spots. By forcing small businesses into bigger spaces, both the investor loses, and the occupant often overpays.

What we see is this: investors need to make overhead. The community wants more green spaces, affordable housing, smaller spaces for new businesses, and third places/community gathering areas. At first, these things can feel at odds. Here’s how it worked out for Wheatland Plaza.

Not quite Utopia, But sort of black magic

So how did they do it? Here are 6 things, all important, but 4-6 are the biggest moves.

Clean it up: Quite literally — scrub the place down. Add fresh paint. Update the signage. These small acts send a powerful signal: this place is open for business right now. It's not just about aesthetics; it's about showing the community that someone cares, that life is returning, and that this forgotten space still holds promise.

Small Bets for activation: Invite food trucks or pop-up events to draw people onto the grounds. Shoppers linger longer when food is an option, and those arriving for a meal may stumble upon stores they’d never noticed before. In this particular case, the mall’s revival required a city allowance for a food truck to take up permanent residence — a rare exception, granted without the typical demand for permanent sewer hookups. It’s a small concession, but one that can breathe life into a space, turning a forgotten parking lot into a place where people gather, linger, and discover something new.

People are attracted to other people. If a place can meet a minimum standard of cleanliness, and the presence of events or food trucks, people who would otherwise skip by this will begin to patronize your businesses. These are a part of a virtuous cycle that compound and build on each other.

Owner-occupied: In Wheatland Plaza, one of the largest spaces developed was a co-working space, which Monte’s real estate company used as its own office. This move not only showed commitment — putting skin in the game — but also secured a reliable tenant: themselves. By designing it as a co-working space, they created an opportunity for future tenants to offset their rent by sharing costs with others. If eventually there is enough demand that they no longer need to occupy it, that’s a win.

Neighborhood Evolution is often telling their clients that sometimes to make the numbers work you have to move it. And that’s definitely a part of what makes this space work.

Break it up: Many of the retail spaces were simply too large — oversized and unwieldy for smaller businesses to manage. For one retailer, the solution was to move them into a smaller, newly renovated space. While they ended up paying more per square foot, they gained a better-designed, more efficient storefront — one that ultimately tripled their sales. The space itself became a better match for its potential.

But beyond resizing individual tenants, subdividing these spaces opens doors to entirely new uses. Look closely at Image 1 — those tiny yellow units? They're compact restaurant spaces, fully equipped with hookups for new and aspiring restaurateurs. This plug-and-play setup lowers the barrier for small businesses to get started and makes it easier to replace tenants if they shutter or move on to larger ventures. In this way, these spaces become more adaptable, more flexible, and more resilient — evolving to match the changing needs of the community.

Last week, Monte was speaking to a room full of developers and said something that felt counterintuitive: be in the business of making your tenants successful. If they succeed, they’ll be better able to afford their rent. Dividing larger spaces into smaller ones can not only increase the amount earned per square foot for the developer but also lower the overall rent cost for small businesses — mitigating risk for both parties.

Add housing: The last and perhaps the most innovative move here was to turn a substantial part of the parking lot into housing. Though initially approved for many more units, ultimately interest rates and the markets made it to where 16 units made sense. Parking lots are almost universally overbuilt and often mostly empty even on the busiest days of the year (except for maybe Trader Joes).

In this case, adding housing enhances outdoor spaces, breaks up the monotony of a blank parking lot, increases housing supply, and creates built-in customers for nearby businesses. Additionally, this particular housing project is being developed in partnership with Habitat for Humanity to ensure affordability.

The results speak for themselves. Although construction on the housing has yet to begin, the most recent bank appraisal for investments valued the property at $25 million — more than eight times its original value. Even more impressive, the value per square acre now exceeds that of almost any commercial space in Duncanville, including being six times more valuable than the nearby Costco.

These numbers matter because they directly impact tax revenue — the funds that pay for firefighters, teachers, and road repairs. While this isn’t an easy "plug-and-play" solution for out-of-town developers, that's not the goal. Instead, this approach empowers local investors — people who genuinely care about the community and will actively contribute to its success — to generate wealth while improving their neighborhood.

Love this reimagining!!! I vote for even more green space and adding a community garden and compost collection center!

A mall here in Kansas city remodeled it's dead anchor store into a row of small units like this that surround a green outdoor common space. They have live music and small events in that space and it's a great place for kids to run around. They set up gas heaters to gather around to extend it's usefulness into the cooler fall and early spring days. Definitely seems like a similar, good approach for these spaces. Also, it provides a third space to the community similar to how the inside of malls were in the 80s and 90s.